History of Tluste/Tovste

from a Jewish Perspective

Introduction

The following pages give an overview of the history of Tluste/Tovste

and of the region in which it is situated from the perspective

of the Jewish population, one of three principal ethnic groups

that co-existed there. Polish and Ukrainian perspectives each

receive their own treatment elsewhere in dedicated overviews;

while the section 'Tluste - Life

and Times' attempts to give an overall impression of what

the town was like between 1880 and 1930.

While their histories are necessarily intertwined, a case

can be made for presenting these ethnic perspectives separately.

For, although they lived side-by-side for many centuries,

persistent tensions among these communities ensured that they

maintained distinct identities and separate affiliations throughout

their long co-existence.

Each of these overviews is a work in progress. They will

be supplemented by additional information as it comes to light.

Indeed, there are many rich sources of historical information

already at hand, waiting to be translated into English from

the original Hebrew, Polish or Ukrainian texts. While no claim

is made that the information presented here is comprehensive,

it should nonetheless give a fairly good sense of the social

interactions, over time, among these three communities.

The Polish Era

From the 14th to 18th centuries, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

expanded to cover a huge territory in northern Europe. During

this period, Tluste was part of the fertile province of Podilia

(also written as Podole in Polish, Podillia in Ukrainian).

Ruthenian (Ukrainian) peasantry made up the vast majority

of the populous, while Jews settled in newly created towns

and were heavily involved in the administration of large tracts

of land granted to noblemen. These formed the basis for the

latifundia, vast estates characterised by primitive agriculture

and indentured labour. (1).

The existence of a Jewish population in Tluste can be documented

at least as far back as the early part of the eighteenth century,

and probably much earlier. Though few, if any, Jews live in

Tovste today, this belies the fact that from at least the

middle of the nineteenth century until well into the first

few decades of the twentieth century, Tluste was predominantly

a Jewish town.

According to Rosman (2)

, the mid-seventeenth century Jewish community of the Commonwealth

enjoyed a large measure of freedom in economic, religious

and internal communal affairs -- owing to a tradition of Polish

tolerance as well as compelling utilitarian reasons. However,

sporadic anti-Jewish violence fostered an undercurrent of

insecurity. This was manifested most dramatically in the peasant

uprising of 1648, led by the Cossack Bohdan

Khmelnytsky, which had profound effects for Podolia and

its Jewish population. Although initiated as a protest by

Cossacks against their treatment by Polish landlords, it was

transformed into a widespread campaign of violence against

anyone identified with the "establishment", particularly Jews

who lived in urban areas (3).

Some estimates put the number of Jewish victims in the whole

of Ukrainian territory at up to fifty percent of the total

population of 40,000 (4).

Though the situation in Podolia eventually stablised, the

last three decades of the century saw further economic and

social decay, as the territory was ceded to the Ottoman Empire

through the 1672 Treaty of Buczacz. It was not until the end

of the seventeenth century, when Poland recovered Podolia

once again, that prosperity began to return. Magnate latifundia

owners solicited Jews and other townspeople to re-establish

life in towns; and a modified Jewish-dominated leasing system

was revived (5).

Rosman (6)

gives a sense of the Podolian environment into which Tluste's

most famous son, the Ba'al

Shem Tov, was born around 1700 — not in Tluste,

but in the village Okupy, near the southern border with Moldavia:

"Culturally, eighteenth-century Podolia was a crossroads.

Each of the three dominant ethnic groups -- Poles, Jews,

and Ukrainians -- had its own language, religious ritual,

and elite culture." Their everyday life -- marked by different

Sabbaths, holidays and even calendars -- made it impractical

for them even to share a meal or celebration together.

On the other hand, "close proximity, familiarity with each

other's lifestyles, business and other utilitarian considerations

and subtle, shared assumptions about reality and the means

for contending with it, all contributed to a situation in

which Jews and Christians found the opportunities and the

means to communicate with each other."

"Jewish-Christian social encounters can be schematised

as occupying a spectrum ranging from antagonistic encounters

during wars, riots, raids, holdups, and casual street physical

and verbal violence through more or less acrimonious but

controlled confrontations in law courts to mildly negative,

neutral, or friendly business, neighbor, and health (or

spirit) care relationships and culminating in real individual

friendships and group wartime alliance and cooperation."

As it happens, the birth of Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer at the

turn of the century coincided with a period of recolonisation

and revitalisation of Podolia, whereas the Commonwealth as

a whole continued its economic decline. Jews took advantage

of the opportunities afforded by this newfound growth and

prosperity; by 1764, their population in Podolia numbered

some 40,000 -- six percent of the total Jewish population of

the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. "Along with everyone in

the region, the Jews benefited from the moderate degree of

stability afforded by magnate rule and the economic boom that

was the effect of recolonization... In Polodia, Jews and Christians

shared the physical, social, cultural, and economic environment,

even if they did not operate in the same universe of discourse."

| Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer chose to settle

in Tluste, around 1734, and to reveal himself there as

the Ba'al Shem Tov. His connection to Tluste is confirmed

by various sources: two of the rare surviving letters

signed by the Besht indicate that Tluste was his home

or place of origin; there are two references to Tluste

in the tales of his life and deeds, depicted in Shivei

Ha-Besht: In Praise of the Baal Shem Tov (7);

and his mother is buried in Tluste's Jewish cemetery,

where her tombstone could be found until the time of World

War II.) |

|

|

One may speculate that there must already have been a modest

Jewish population in Tluste for the young rabbi to have chosen

to settle there. Indeed, a census conducted in 1764, three decades

after the Besht's revelation, indicated that there were then

355 Jewish residents of Tluste and surrounding villages (8).

Under Austrian Rule

In 1772, the vast territory that had been the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth was subjected to the first of three partitions

that would take place before the end of the century. The Austrian

Empire absorbed Polish territory that would become the new

province of "Galicia and Lodomeria", more commonly known as

"Galicia", so-named after the historic Ukrainian appellation

for the region, and its ancient capital of Galicz (Halicz).

Tluste was thus included in this expanded Austrian Empire,

and would remain so until 1918.

The reign of Empress Maria Theresa and her successors through

to Emperor Ferdinand, who abdicated in 1848, was fraught with

difficulties and ineffectual reforms -- partly a consequence

of having to deal with many divergent ethnic interests. Jews

were said to have fared better under the 68-year reign -- from

1848 to 1916 -- of Franz Josef, who reformed the restrictive

and harsh policies of his predecessors and sought Jewish allies

in his efforts to retain control of Galicia.

In the nineteenth century, the Jews of Tluste traded in agricultural

produce, timber, cloth, and beverages. Hasidism was preponderant

in the town. The wealthy members of the community (estate

owners, contractors and merchants of forest products and hides)

were followers of the zaddik of Chortkov (a town

20 km to the north), whereas shopkeepers, grain merchants,

brokers and scholars adhered to Viznitsa Hasidism, and the

artisans were followers of the zaddik of Kopychintsy

(9).

The growing importance of the Jewish population in Galicia,

as a whole, during Austrian rule is reflected in statistics

compiled in the framework of the 1880 census (10).

The percent of Jewish pupils in Gymnasien and Realgymnasien

rose from about 6 percent in 1851 to nearly 20 percent by

1880, with much of that growth occurring in the last six years

of the survey period (i.e. 1874-1880).

The picture for Realschulen was somewhat different,

with Jewish pupils already constituting a relatively high

percentage (i.e. close to 20 percent) of the school population

from the early 1850s. Apart from a 7-8 year lull — from

1868 to 1874 — when this figure dropped to as

low as 10%, the percentage of the overall school population

remained relatively high throughout the 30-year period, and

stood at 23 percent in 1880. In absolute terms, the highest

enrollment was achieved in 1877, when 377 of 1557 Realschulen

students in Galicia were reported to be of Jewish origin.

Between 1880 and 1930, the population

of Tluste grew steadily from 3,285 individuals to a peak

of about 4,000; while that of the town and the suburbs together

grew from 6,000 to just over 8,000. What is most remarkable

about these figures is the clear indication that, during this

period, Tluste was predominantly a Jewish town. Jews consistently

made up approximately two-thirds of the population, while

Ukrainians constituted about 20-30% and Poles only 11-12%.

Contrasting the composition of Tluste proper, the smaller

surrounding villages were made up primarily of Ukrainians

(roughly three-quarters) and Poles (20-25%). Jews constituted

less than five percentage of their population and virtually

all of them were tradesmen, shopkeepers and their families.

This clear tendency for the Jewish community to concentrate

in towns, rather than smaller villages, was common elsewhere

in Galicia. The 1764 census of Polish Jewry, mentioned earlier,

indicates that there were already 251 Jews living in Tluste

alone. At that time, a relative large proportion of the total

Jewish population (about 30%) lived in surrounding villages,

but over the next one hundred years there was an obvious migration

towards Tluste proper.

|

|

The prominence that the Jewish community

had attained in Tluste by the mid-nineteenth century

is revealed in the earliest known map of the town, a

precise Austrian document dating from 1858.

The central market area of town -- surrounding the Catholic

church -- was comprised mainly of Jewish-owned shops

and businesses, selling food, fabric and other household

goods. |

| |

|

|

| A synagogue

(centre of photo) stood on the opposite side of the

main road through town, close to the northern end of

the reservoir.

All of these buildings appear again in another Austrian

map prepared in 1899. By that time, the Jewish population

of Tluste had grown to nearly 2,500 residents. |

|

|

The 1891

Galician Business Directory lists the occupations of about

70 individuals engaged in commercial activities in Tluste towards

the end of the nineteenth century

(11). Most of the family names in the list appear to be

of Jewish, Polish or German origin; the list contains few if

any Ukrainian-sounding names. Members of the Jewish community

were involved in all facets of the town's livelihood -- in the

food and service sectors, as dealers of raw materials and hardware,

in retail establishments, and as tradesmen and professionals.

Notwithstanding the relative prosperity that they evidently

enjoyed, Tluste's Jews also took part in the wave of emigration

from Ukraine to America that occurred around the turn of the

century. "Economic distress, epidemics, anti-Semitism and

a desire for a better life led many Jews to emigrate from

Galicia in the last years of the nineteenth and the early

years of the twentieth century" (12).

In New York, in 1898-99, Jewish immigrants from Tluste established

and incorporated a fraternal mutual aid society, known as

a Landsmannshaft. A number of these Landsmannshaften

were created by immigrants from Tluste/Tovste, and at

least one - the Young Tluste Society - continues to operate

today. (One can observe in Wellwood Cemetery, Pinelawn, New

York, a memorial

erected by the Tluste Society in remembrance of families

who perished in Tluste and vicinity.)

With the onset of the First World War, Russian soldiers occupied

Tluste in the second half of 1914. Jews suffered at the hands

of the Russians during the wartime occupation. According to

Pawlyk, local people were frightened and wary of the arrival

of the Russians, and expected them to be cruel -- to murder

Ukrainians, especially Jews, many of whom fled to Vienna.

Local people decided to put icons in the windows so that the

Russians could see that they were not Jewish. The occupiers

forced Jews to work to maintain order and to keep the town

clean but soon, through bribing, the Jews began to co-operate

with them (13).

Apparently the Russians were constantly in search of vodka,

which the Tsar had prohibited at the beginning of the war

.

Tluste and surrounding areas changed hands a number of times

during the war. Some time in the winter of 1914-15, the Austrians

managed to drive out the Russian army. Pawlyk reports that

in the summer of 1915 the front line was further along, on

the Dniester river. There, the Austrian army used bacteriological

weapons, which killed first the soldiers and then people in

villages and towns along the river. Many soldiers sick with

cholera were brought to Tluste hospital, which was located

close to the railway station. Those sick soldiers usually

died within several hours. They were buried in a separate

"cholera cemetery", which was established near the Jewish

quarter. Soon, many local people -- especially Jews -- were

infected, and a sanitary service was organised.

Having been driven out of the area in the autumn of 1915,

the Russians returned in June 1916 and remained in the Tluste

through July 1917. The war ended in 1918 with the downfall

of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire.

The Inter-war Years

Writing about history of the region and the village of Suchostaw,

located about 35 km north of Tluste, it was noted that by

the aftermath of the First World War, the best days for Galician

Jews were probably behind them (14):

"After the War, the Jews remaining in the region found

themselves in a much changed position. Instead of the considerable

civil rights they had held in the multinational Austro-Hungarian

Empire, they now found themselves a minority in a devastated

area of newly independent Poland. Here political and economic

power resided with the Polish minority who were none too

interested in sharing it with the resident Jewish population.

Neither were the local and dominant population of Ukrainian

peasants any less hostile to Jews. Soon Polish authorities

banned Jews from government posts, boycotted Jewish businesses,

imposed new taxes, and restricted Jewish entry into high

schools and universities. A sense of despair was felt in

shtetlach throughout the region.

The Jewish response was varied: labor organizations were

created, Zionist groups took hold, mutual aid and economic

support associations were created."

In Tluste, the Jewish population maintained

itself, reaching a peak of 2,600 by 1930, the last year

for which complete census data are available.

According to Encyclopedia Judaica (15),

"all the Zionist parties were active in the town and

there was a Tarbut Hebrew school" (pictured at right).

|

|

|

Tluste and the Holocaust

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, the Jewish

population of Tluste had already declined to less than 1200,

fewer than half the number of residents recorded at its peak

in 1930. (In his 1996 survey of the Jewish cemetery of Tovste

(16),

Hodorkovskiy Yuriy Isaakovich quotes a figure of 1,196 Jewish

residents of the town in 1939; whereas Encyclopedia Judaica

(1972) attributes this same figure, apparently incorrectly,

to 1921.)

With the fall of Poland in September 1939, Soviet forces

occupied Tluste and neighbouring towns. They remained there

until June 1941, when Nazi Germany commenced hostilities against

the Soviet Union. Tluste was captured by the Hungarian army,

which was an ally of Germany. Groups of Jewish youth attempted

to escape to the USSR with the retreating Soviet army, but

only a few succeeded (17).

Over the next three years, until Tluste was once again "liberated"

by Soviet forces, unspeakable horrors were perpetrated on

the Jewish community.

|

|

In 1961, more than 50 former residents

of Tluste participated in the publication of a memorial

volume to commemorate their experiences. Published by

the Tluste Organization in Israel and the "Landsmannschaft"

in the United States, "Sefer Tluste" (18)

contains a unique collection of reminiscences of Jewish

life and death in Tluste. The complete volume can be

accessed online through the

New York Public Library website.

|

The introduction to "Sefer Tluste" explains:

"Tluste was the last city in Eastern Galicia to undergo

the process of total extermination, so it contained those

Jews who had survived earlier "Aktions" in the

neighbouring towns. Out of the three thousand Jewish residents

of Tluste and the thousands of refugees from the neighbouring

towns, less than five hundred survived at the end of the

Second World War.

Immediately following their arrival the Germans commenced

their cruel and merciless oppression of the Jewish inhabitants.

Decrees restricting Jewish freedom of movement and preventing

the Jews from continuing their normal lives were enacted

almost daily. They were followed by the murder of isolated

Jews, and finally came the massacre of thousands of Jewish

residents of Tluste and the vicinity."

The following description of what happened in Tluste between

1941 and 1943 is derived largely from the account of a Jewish

doctor, Baruch Milch,

who survived the systematic extermination of Jews from the

town. His compelling story is told through an edited diary

that came to be published as a book, Can Heaven be Void?

(19).

It was released in three different language versions

(Hebrew, Polish and English) between 1999 and 2003. Where

instructive, information to supplement that of Dr. Milch is

provided from other sources.

The Beginning of the End

In June 1941, in the face of the German advance, the Soviets

pulled out of Tluste amidst incessant air raids. Pandemonium

and uncertainty reigned, as a Ukrainian mayor was installed

and a "settling of accounts" began. In Tluste and in other

villages and towns, rioting mobs of vengeful Ukrainians looted

houses and murdered Jews. After some time, soldiers of the

Hungarian army, allied with the Germans, arrived in town and

continued the plunder (20).

Towards the end of June and beginning of July 1941, a German

air and ground offensive hastened the Soviet retreat from

Zalishchyky, 25 km south of Tluste. The Russians destroyed

the railway bridge in the process in order to impede the German

advance (21),

but the town was captured anyway on 8 July 1941 (22).

The Germans eventually made their way to Tluste, passing through

the town from two directions (Czortkow and Borszczow), en

route to the north and east (23).

A small German force, including SS men, was installed in Tluste

to engage the retreating Soviets. It is thought that the explosion,

around that time, of a train full of arms at Tluste station

was an act of sabotage by the retreating Soviet forces (24).

In July-August 1941, a German officer became military governor

of Tluste; and the organised and systematic persecution of

Jews by the Nazis began in concert with a local Ukrainian

committee appointed by the occupying force (25).

It is written, more generally, that some Ukrainians expected

to be rewarded for their collaboration, with an independent

Ukraine. However, their hopes for statehood were dashed within

a couple of months when the Germans made it clear that there

would be no independent Ukraine. Rather, Galicia would be

an integral part of the German-occupied sector of Poland,

the Generalgouvernement (26).

| A nightly curfew was imposed in Tluste and

freedom of movement of Jews was curtailed. Around August

1941, the Germans set up a Judenrat (Jewish council)

under chairmanship of a Dr. Aberman, together with a Jewish

police force, in order to impose order, persecute the

Jewish community and facilitate mass deportations. |

|

|

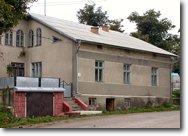

The Judenrat, housed in the building pictured above,

was guarded at night by Jewish policemen bearing the Star

of David on their uniform. Anti-Jewish edits were issued (imposing

forced labour, wearing of the Star of David, restricting movement

etc.) and periodic joint Gestapo-Ukrainian police raids begin,

characterised by searches of houses, beatings, arrests, murders,

and confiscation of property (27).

Similar scenes of persecution perpetrated by German soldiers

and Ukrainian collaborators were repeated in nearby towns.

In July, the killing of Jews and looting of homes began in

Czortkow, less than 20 km north of Tluste (28).

A Gestapo headquarters was established there, from where control

over Tluste would be exerted throughout the Nazi occupation.

From time to time, the Gestapo would travel to Tluste in a

black vehicle that came to presage arrests, extortion and

murder (29).

In Horodenka, about 20 km to the southwest, a reign of terror

followed the German occupation in July 1941, beginning with

anti-Semitic proclamations and deportations of Jews. A ghetto

was established there around October 1941 (30).

By September, the whole of Zalishchyky region had been occupied

and was administered by the Hungarian allies of the Germans.

In November-December 1941, there was a mass slaughter of Jews

near Zalishchyky (31)

and another of Horodenka Jews at Siemakowce (32).

Beginning around March 1942, a ghetto was established in

Tluste to which the remnants of Jewish communities from neighbouring

towns and villages were brought, prior to systematic deportations.

The Holocaust Chronicle website documents these expulsions

with photographs from the United States Holocaust Memorial

Museum Photo Archive:

Photo 1 and Photo

2. At some point, there was a forced influx of stateless

Jews expelled from Hungary and elsewhere. Arriving over a

two-week period on columns of trucks under the guard of Hungarian

soldiers, the refugees were robbed of their possessions and

many were killed when in the process of trying to return home

(33).

|

|

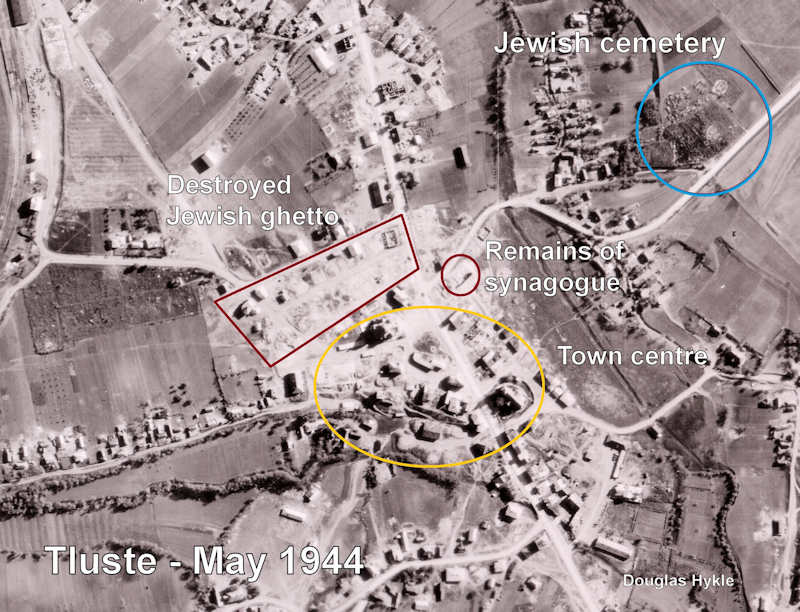

As shown here, in an aerial photograph of

the town centre, taken by German reconnaissance aircraft

in May-June 1944, the ghetto created after the 27 May

1943 Aktion was located on two streets adjacent to (northwest

of) the Greek Catholic Church.

Click on photograph to enlarge. |

Judenrat policemen collected money to buy food for

the ghetto prisoners -- cheese, bread, milk, meat, onions,

and even vodka (34).

People were crowded into small houses assigned by the

Judenrat, sometimes with as many as four or five families

living in a single room.The sanitary conditions were appalling,

and food was scarce (35).

Stars were placed on the doors of houses where the Jews lived;

this way the entire Jewish population was controlled.

At some point during this period, the mostly Jewish-owned

shops in the centre of Tluste were torn down and the wood

used for scrap. In the photo above, just to the north of the

Greek-Catholic cathedral, one sees only faint remnants of

the foundations where buildings once stood. Further to the

east, the stone edifice that had been used as a synagogue

for at least a half century (and previously as a fort, for

even longer) was also demolished. Only the rear wall remains

visible.

In Spring-Summer 1942, Jews were sent to labour camps in

vicinity of Tluste, such as the one at Lisowce (Lisivtsi).

Many were engaged there in the manufacture of synthetic rubber

from the plant called kok-saghys (36).

The first major, overt Aktion in Tluste took place

in August 1942, apparently intended to make up the shortfall

in a neighbouring town's "quota" of Jews to be deported (37).

On 27 August, the Germans ordered the Judenrat to

round up 300 people, who were then dispatched to Belzec (38)

by train. Smaller Aktionen followed repeatedly in

the coming months, in which armed Gestapo men would surround

the Jewish quarter and, helped by the Judenrat, rouse

people from their homes. Those who were not shot on the spot

for resisting or trying to flee were then assembled and crammed

onto trains, which carried them to their fate (39).

Baruch Milch reports that in between these periodic Aktionen,

Judenrat officials took advantage of the climate

of fear among the Jewish population to carry out acts of extortion.

"People changed beyond recognition and were ready to do anything

to survive, often at the expense of others, including relatives.

The real culprits, however, were those who had brought us

to this pass" (40).

People attempted to prepare hiding places in which to conceal

themselves during the successive Gestapo raids. See, for example,

'The Spitzer Story'.

On 20 September 1942, the Germans expelled Zalishchyky's

Jews to neighbouring ghettos; and most were sent to Tluste

(41). Similarly, in Horodenka, a 3-day Aktion

ended with the town being declared Judenfrei (free

of Jews) and any survivors were ordered to leave within 24

hours (42).

The following month, on 5 October, there was a second major

Aktion in Tluste and nearby villages. According to

Baruch Milch, who had been forewarned about the impending

raid, 1000 Jews were deported from Tluste and 120-200 or more

were killed in town (43).

It was said that the horrific scene of death and looting resembled

the aftermath of a pogrom.

During the winter of 1942-43, periodic expulsions from surrounding

towns continued, and Jews were increasingly concentrated in

ghettos. Amidst conditions of congestion and starvation, typhus

epidemics broke out in the ghetto of Tluste and elsewhere,

claiming 6-8 lives daily (44).

In an excerpt from her poignant memoir, "A Horodenka Holocaust

Memoir", Tosia Szechter Schneider recalls her experiences

in the Tluste ghetto:

"My mother, my brother, and I found ourselves in the ghetto

of Tluste. The winter of 1942 took a terrible toll from

starvation and typhus. That winter my mother made a last

attempt to save me. She met a Ukrainian man who said that

he would be willing to get for me false papers and to take

me to a far-away village to his cousin. My mother was overjoyed,

we knew we were all doomed. She spent two days teaching

me the catechism and how to behave in church. Every time

my resolve weakened but she kept repeating "someone must

survive to tell the world". Our greatest fear was that we

will all be killed and no one will know of the evil deeds.

I said good-bye to my brother and walked with my mother

to the end of the ghetto, I was to take off my armband and

steal across the gate. I was only 14 then but I thought

that all our people will be destroyed, and why would I want

to live in a world without Jews, and be part of a people

who, if not active participants in the murder of my people,

certainly stood idly by. I decided that it was not worth

it, to my mother's great dismay, and decided not to leave.

She did not urge me, she knew how uncertain that attempt

was, and we walked back to the ghetto.

I have never regretted that decision; in spite of the hunger

and suffering, I had a few more short weeks with her. My

mother contracted typhus and, at the age of 39, died of

starvation and disease.

We were left four children all alone; the oldest was my

cousin Bella, 17. I also became very sick with typhus and

I don't remember much of that winter. My brother credited

my survival to the "miracle" of the eggs: a Polish man who

lived close to the ghetto and who at one time worked with

my father, found out about us, and brought us eggs, practically

the only food we had, plus the meagre ration. But more than

sustenance, he brought some light of human kindness into

that world of darkness and despair."

Raids and killings continued through the winter, albeit on

a smaller scale, it would appear. O'Neil (45)

reports that on 12 February 1943, 40 Jews were shot in Tluste.

After a period of relative calm around the time of Passover,

in April 1943, news came of an Aktion in a nearby

town, heightening fears that Tluste would be next. Baruch

Milch suggests that there was to have been an Aktion

in Tluste then, but the Gestapo came and went after discovering

that nearly all of the Jews had dispersed throughout the area,

in anticipation of trouble (46).

The short reprieve, if one can call it that, continued for

a while, at least for some Jews who were able to secure documentation

permitting them to work as labourers in nearby camps. According

to Baruch Milch:

"The central nervous system of the area was our town, Tluste,

where one of the region's five Jewish communities lived.

Since ours was not a true ghetto, Jews enjoyed greater freedom

of movement in Tluste than elsewhere. Therefore, only some

1,800 of 5,000 Jews in the community were registered with

the authorities. The surrounding farms needed and found

many working hands, and a camp known as "W" (for Wehrmacht)

was built two kilometers from town for the families of "privileged"

Jews, particularly those close to the Judenrat.

... The Judenrat stepped up the transfer of able-bodied

Jews to the camps and invoked all kinds of ruses to save

their cronies." (47)

The End

Amidst rumours of bloody Aktionen in nearby towns,

the third major Aktion in Tluste began in the early

hours of the morning of 27 May 1943. This horrific event would

effectively bring to an end the centuries-long presence of

Jews in Tluste. The Germans, supported by Ukrainian and Jewish

police, deployed around 1:00 or 2:00 a.m. For the next 20

hours, a contingent of about 300 men went from house to house,

rounding up Jews and slaughtering those who resisted. Ironically,

some who hid in improvised hideouts survived, whereas those

in more elaborate bunkers were discovered.

People were led to the town square where they were forced

to hand over their valuables. Able-bodied men were taken to

the Jewish cemetery to dig pits that would ultimately serve

as mass graves for the victims. Later in the afternoon, beginning

around 4:00 p.m., the captives were led in groups of 100 to

the cemetery. It is said that a Jewish musician in town, by

the name of Stupp, led the slow processions to the cemetery

while playing solemn music on his violin (48).

In a 2004 interview, an elderly resident of Tovste, who would

have been in her mid-teens at the time, described the massacre

as others — who had witnessed it first-hand —

had recounted it to her. She said that the Jews were ordered

to stand on planks of wood above the pits, into which they

fell after being shot. Not all of them died instantaneously.

It was said that the earth in which they were buried was seen

to move, as though some poor souls had been buried alive.

The woman recalled the villagers being perplexed as to why

the Jews did not attempt to escape from the ghetto, as would

have been possible, at least for some. She claimed that, in

response, one old man said that they were resigned to their

fate, being of God's will, and that "our blood will be on

you and on your children".

When the shooting finally ended around 9:00 in the evening,

it is estimated that from 2,000 to 3,000 Jews had been murdered.

A Gestapo officer was reported to have directed the whole

operation, and personally took part in the shootings at the

cemetery (49).

|

|

An aerial photograph of the cemetery

on the outskirts of town, taken by German reconnaissance

aircraft a year later, in June 1944, confirms this atrocity.

The Jewish cemetery is situated in the upper right

hand corner of this photograph. In the enlargement (viewed

by clicking on the image), one observes row upon row

of densely packed tombstones.

|

Amidst an area containing 25 or so rows of tombstones, there

is a large circular clearing towards the road where one can

make out the outline of two rectangular shapes. Further in

from the road, to the northeast, there is another circular

clearing surrounding what appears to be single, large rectangular

shape. It is believed that they contain the remains of the

victims of the 27 May 1943 massacre.

For Tluste, the last act of the 'Final Solution' played out

around 6 June 1943. That morning, Gestapo men and Ukrainian

surrounded the ghetto, and proceeded to shoot or bludgeon

to death many of the Jews who had survived the Aktion

ten days earlier. By this point, their hiding places were

insufficient, having been detected during previous raids.

The following day, the order came to purge Tluste of Jews

and declare the town Judenrein within two days (50).

It is reported that 1,000 Jews were killed or deported from

Tluste at that time (51).

The Sefer Tluste (52)

picks up the threads of the story:

"About two months later [i.e. by around August 1943] in the

town was declared "Judenrein" (cleared of Jews) and

no Jew had the right to be there. The handful who had escaped

death hid in forests or labour camps in the surrounding villages.

However, the residents of the camps were also liable to sudden

attacks by the Gestapo or the Ukrainian police, who collaborated

with the German murderers helping them to exterminate the

Jewish population."

Baruch Milch emerged from hiding in Czerwonogrod and returned

to Tluste some eight months later, at the end of March 1944.

Though the town was almost unrecognisable, he discovered that

some 200 or so Jews had actually survived in the labour camps

or from other hiding places (53).

"Many of the Jews who had fled to the forests fell into the

hands of the fanatic Ukrainian Bandera gangs, but some of

them joined partisan units. The remnants of the community

were liberated from the camps in the area in March 1944" (54).

Soviet forces regained at least partial control over the

region in the latter part of March and first half of April

1944. The Germans pulled out of Tluste during this time, but

a large contingent of soldiers, part of a force retreating

to the west, reoccupied the town for about a week before finally

heading towards Buczacz. The Soviets regained effective control

of Tluste on 13 April 1944 (55).

Jewish life was never reconstituted in

Tluste after the war. A memorial to these tragic events

can be found in what remains of the town's Jewish cemetery.

The Hebrew inscription, translated into English (56),

reads:

"In memory of the martyrs of Tluste and surroundings

who were annihilated by the Nazis in the years 1942-1943

and to remember all the martyrs who are buried in this

cemetery. Erected by the survivors from Tluste." |

|

|

* * * * *

Much more could be written about the contribution of Tluste's

Jewish population to the life of the town. The Sefer Tluste

memorial book is an extremely rich source of information.

The original texts (in Hebrew and Yiddish) have now been completely

translated into English, and are available for viewing on

the website of JewishGen. Click here

for more details of this long-lasting effort.

Over the past decade, I have reviewed hundreds of written

and oral testimonials from Shoah survivors associated with

Tluste -- sourced from archives and other research institutions

in the United States, Israel, Poland, Germany, and Austria

-- and I have interviewed dozens of survivors from the town.

Eventually, the material from this exhaustive research will

find its way into a substantial publication.

Notes:

(1) Rosman, M.J. Founder of Hasidism: a quest for the

historical Ba'al Shem Tov. Berkeley, 1996. p. 44.

(2) Ibid. p. 44.

(3) Ibid. p. 44.

(4) Stampfer, S. "What actually happened to the Jews of

Ukraine in 1648?" in Jewish History. 17: 207-227

(2003). p. 207.

(5) Rosman, M.J. Founder of Hasidism: a quest for the

historical Ba'al Shem Tov. Berkeley, 1996. p. 52.

(6) Ibid. p. 56-62.

(7) Ben-Amos, D. and J.R. Mintz (eds). In praise of

the Baal Shem Tov (Shivhei ha-Besht). Northvale, N.J.,

1993.

(8) Stampfer, S. "The 1764 Census of Polish Jewry" in

Bar-Ilan / Annual of Bar Ilan University Vol. 24-25.

p. 135.

(9) Encyclopedia Judaica. Jerusalem, 1972. Last

accessed via the Museum of Tolerance Multimedia Learning Center,

https://motlc.learningcenter.wiesenthal.org/text/x32/xr3263.html

on 18 August 2005.

(10) Statistische Monatschrift. VII. Jahrgang. Wien

1881. p. 448-51.

(11) The 1891 Galician Business Directory (Kaufmannisches

Adressbuch fuer Industrie, Handel und Gewerbe, XIV. Galizien,

published by L. Bergmann & Comp., Wien IX, Universitutmetr.

6): https://www.jewishgen.org/databases/Poland/galicia1891.htm;

last accessed on 14 August 2005

(12) "Summary of History of the Suchostaw Region": https://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/Suchostaw/suchhistorysummary.html;

last accessed on 16 August 2005.

(13) Pawlyk, J. History of Tovste. Chortkiv, 2000.

p. 48-50.

(14) Summary of History of the Suchostaw Region: https://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/Suchostaw/suchhistorysummary.html;

last accessed on 16 August 2005.

(15) Encyclopedia Judaica. Jerusalem, 1972. Last

accessed via the Museum of Tolerance Multimedia Learning Center,

https://motlc.learningcenter.wiesenthal.org/text/x32/xr3263.html

on 18 August 2005.

(16) International Jewish Cemetery Project: https://www.jewishgen.org/cemetery/e-europe/ukra-t.html;

last accessed on 16 August 2005.

(17) Encyclopedia Judaica. Jerusalem, 1972. Last

accessed via the Museum of Tolerance Multimedia Learning Center,

https://motlc.learningcenter.wiesenthal.org/text/x32/xr3263.html

on 18 August 2005.

(18) Lindenberg, G. (ed.). Sefer Tluste. Tel Aviv,

1965.

(19) Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.). Can Heaven be Void?

Jerusalem, 2003.

(20) Ibid. p. 73-5.

(21) Lecker, M. "I Remember: Odyssey of a Jewish Teenager

in Eastern Europe". In Montreal Institute for Genocide and

Human Rights Studies. Volume 5. https://migs.concordia.ca/memoirs/lecker/lecker.html;

last accessed on 14 July 2005.

(22) Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: "Zalishchyky" - Encyclopedia

of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume II (Ukraine), pages

195-199. https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/pinkas_poland/pol2_00195.html;

last accessed on 18 August 2005.

(23) Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.). Can Heaven be Void?

Jerusalem, 2003. p. 75

(24) Pawlyk, J. pers. comm.

(25) Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.). Can Heaven be Void?

Jerusalem, 2003. p. 75.

(26) Ibid. p. 82.

(27) Lecker, M. "I Remember: Odyssey of a Jewish Teenager

in Eastern Europe". In Memoirs of Holocaust Survivors in Canada.

Volume 5. https://migs.concordia.ca/memoirs/lecker/lecker.html;

last accessed on 14 July 2005.

(28) Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.). Can Heaven be Void?

Jerusalem, 2003. p. 88.

(29) Szechter Schneider, T. "A Horodenka Holocaust Memoir".

https://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/Gorodenka/html/holocaust_memoir.html;

last accessed on 9 February 2010.

(30) Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: "Zalishchyky" - Encyclopedia

of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume II (Ukraine), pages

195-199. https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/pinkas_poland/pol2_00195.html;

last accessed on 18 August 2005.

(31) Schneider, T. "Visiting Horodenka, Fifty-three Years

Later". https://www.geocities.com/mrheckman/gorodenka/tschneider.html;

last accessed on 18 August 2005.

(32) Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.). Can Heaven be Void?

Jerusalem, 2003. p. 77, 88.

(33) Ibid. p. 79-80.

(34) Pawlyk, J. History of Tovste. Chortkiv, 2000.

p. 50.

(35) Schneider, T. pers. comm.

(36) Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.). Can Heaven be Void?

Jerusalem, 2003. p. 89.

(37) Ibid. p. 97.

(38) See also https://www.deathcamps.org/belzec/galiciatransportlist.html

(39) Ibid. p. 98-100.

(40) Ibid. p. 110.

(41) Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: "Zalishchyky" - Encyclopedia

of Jewish Communities, Poland, Volume II (Ukraine), pages

195-199. https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/pinkas_poland/pol2_00195.html;

last accessed on 18 August 2005.

(42) Szechter Schneider, T. "A Horodenka Holocaust Memoir".

https://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/Gorodenka/html/holocaust_memoir.html;

last accessed on 9 February 2010.

(43) Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.). Can Heaven be Void?

Jerusalem, 2003. p. 102-3. (See also https://www.deathcamps.org/belzec/galiciatransportlist.html).

(44) Ibid. p. 105-6.

(45) O'Neil, R. Unpublished Manuscript and Introduction:

"A Reassessment: Resettlement Transports to Belzec, March-December

1942". https://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/belzec/belzec.html;

last accessed 18 August 2005.

(46) Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.). Can Heaven be Void?

Jerusalem, 2003. p. 112-13.

(47) Ibid. p. 114.

(48) Pawlyk, J. pers. comm.

(49) Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.). Can Heaven be Void?

Jerusalem, 2003. p. 121-131.

(50) Ibid. p. 138-41.

(51) O'Neil, R. Unpublished Manuscript and Introduction:

"A Reassessment: Resettlement Transports to Belzec, March-December

1942". https://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/belzec/belzec.html;

last accessed 18 August 2005.

(52) Lindenberg, G. (ed.). Sefer Tluste. Tel Aviv,

1965.

(53) Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.). Can Heaven be Void?

Jerusalem, 2003. p. 228.

(54) Encyclopedia Judaica. Jerusalem, 1972. Last

accessed via the Museum of Tolerance Multimedia Learning Center,

https://motlc.learningcenter.wiesenthal.org/text/x32/xr3263.html

on 18 August 2005.

(55) Milch-Avigal, S. (ed.). Can Heaven be Void?

Jerusalem, 2003. p. 231.

(56) Schneider, T. "Visiting Horodenka, Fifty-three Years

Later". https://www.geocities.com/mrheckman/gorodenka/tschneider.html;

last accessed on 18 August 2005.

|